THE FUNCTION OF CREATIVITY (esp the ARTS THERAPIES) IN HEALING FROM TRAUMA

In his article in Healing Trauma (2005), Siegel shows how our brains are social organs, and that social interactions are one of the most important forms of experience that shape brain development and give rise to the mind (Siegel, 2005, p.18). One of the most powerful drives of the human mind is the search for meaning, and neurobiology now reveals that the brain processes involved in self-regulation, the creation of meaning and interpersonal communication share overlapping neural circuitry. Emotion and the creation of autobiographical memory are mediated by the same circuits. The implications of this led Siegel to propose that we begin to let go of the “single skull view” of brain and mind, and embrace the concept of the “social brain”.

The brain becomes literally constructed by interactions with others. As we participate in the ‘co-construction’ of each other’s minds, intimately sculpting the unfolding of our mutually created life stories, we find that our most intimate personal processes such as self, are actually created by our neural machinery, which is, by evolution, designed to be altered by relationship experiences. Thinking of minds in this interpersonal and neurobiological way gives us the conceptual foundation in which we can smoothly shift our focus between neurons and narratives.

Siegel (2005), p.18-19

The significance of this for the understanding of trauma lies in the fact that traumatic damage impairs a number of functions in the brain that prevents the resolution of the trauma. Specifically it “impairs the capacity to integrate a range of cognitive processes into a coherent whole” (Siegel, 2005, p.16). It affects integration of memory, development of the sense of self, ability to self-soothe, ability to partake in human relationships, ability to respond flexibly in new situations, and sequelae that are too numerous to detail in this brief introduction (Siegel, 2005, pp.16-17 & 28; Schore, 2005, pp.122-23; van der Kolk & Saporta, 1993; and Lewis Herman, 1992).

Central to Siegel’s story about neural integration in trauma healing, is the role played by the orbitofrontal cortex, which seems to be a convergence area linking systems involved in emotional regulation, self consciousness, memory representation, meaning-making, social cognition and emotionally attuned communication (Siegel, 2005, p.27). It spans the region behind the eyes, and exists in both right and left hemispheres. Neuroscientists have proposed that encoding of information takes place in the left orbitofrontal region and retrieval in the right. The encoding of memory is integral to this process, which is achieved through REM sleep and dreaming. Such ‘cortical consolidation’ allows for the creation of a coherent sense of oneself and a sense of one’s life having an autobiographical narrative.

Such narratives reflect an internal, nonverbal process of neural integration which may become ultimately expressed in words. Coherent narratives – nonverbal or language based – emerge from such a bilaterally integrating process. The process of bilateral integration can thus be proposed to be one of the core elements in resolution.

Siegel (2005), p.28-29

This neuronal integration is essential for a healthy functioning system, but Siegel proposes that “at the core of ‘unresolved trauma’ is an impairment in a core process of neural integration” (p.28). While the achievement of coherent narrativisation is fundamental to most forms of psychotherapy, Siegel is not referring simply to the verbalising we think of when we use the word ‘narrative’. He makes it clear that the integration across hemispheres is of representations or mental images, which may be manifested in an array of sensory modalities, and that the interpersonal therapeutic environment of safety and secure attachment ‘may be essential for the integrative processes to occur.’(p.29) This emphasis on multimodal sensory activities is explained partly by the fact that the left and right sides of the brain speak different languages, the left cognitive, logical and language-based, but always trying to make sense of information it receives, the right intuitive, mentalizing, grasping relationships and acting to represent information non-verbally (Siegel, 1999, pp.326-7). Multimodal creative arts help to bypass this language barrier:

Since the right hemisphere is nonverbal, the output of its processing must be expressed in non-word-based ways, such as drawing a picture or pointing to a pictorial set of options to make its output known to the external world.

Siegel (1999) p. 327

Finally, Siegel suggests how this integration might happen not only in an abstract psychological sense, but in physical reality, in the neuronal pathways and circuits of the brain. In The Developing Mind, Siegel had explained that the neural axons and synapses that form neural pathways are produced by the laying down of protein molecules following gene activation (Siegel, 1999, p.14). In Healing Trauma, he expands on this :

Experience can be defined as the activation of neural firing patterns in response to an internal or external stimulus. We now know that neural activation, under certain conditions, can actually lead to the turning on of genes leading to a cascade of biochemical changes in the neural cell that eventually enables proteins to be produced . . . which enables neural connections to be altered.

In other words, experience . . . can activate genes (leading to protein production) and therefore change brain structure. . . . Experience in general alters the mind by changes in the synaptic connections among neurons. As clinicians, our goal is thus to explore the ways in which the therapeutic relationship may be able to create lasting changes in our patients by way of changes in neural connections.

Experiences, theoretically, should be able to change brain structure, not merely brain function.

Siegel (2005), p.17

APPLYING ‘NEUROBIOLOGY and CREATIVE ARTS’ TO THE THERAPY PROCESS

RIGHT HEMISPHERE COMMUNICATION

Multimodal forms of creativity can serve as forms of communication. Communication is the transmitting of information via any medium, from the sender to the receiver. The receiver decodes the message and may transmit some kind of response. In this discussion such communication is from one (buried) part of self to another, conscious  part. Such messages may be verbal (using language), but may be non-verbal (body or facial language, visual imagery, movement/dance or sound media). Our right hemisphere is specialized to deal with non-verbal communication (facial expression, body language, tone of voice, as well as imagery, symbols and emotions). The right hemisphere processes experience holistically, ie, creating the gist or overall context of experience and the overall meaning of events. The ‘language’ of the right hemisphere is imagery, rather than words, and visual-spatial reality rather than abstract intellectual concepts. Most importantly in this discussion, the right hemisphere is involved in the retrieval of autobiographical memory.

part. Such messages may be verbal (using language), but may be non-verbal (body or facial language, visual imagery, movement/dance or sound media). Our right hemisphere is specialized to deal with non-verbal communication (facial expression, body language, tone of voice, as well as imagery, symbols and emotions). The right hemisphere processes experience holistically, ie, creating the gist or overall context of experience and the overall meaning of events. The ‘language’ of the right hemisphere is imagery, rather than words, and visual-spatial reality rather than abstract intellectual concepts. Most importantly in this discussion, the right hemisphere is involved in the retrieval of autobiographical memory.

The left hemisphere, on the other hand, specializes in the processing of language and linear narratives. It looks for cause and effect relationships to explain the rightness or wrongness of things (syllogistic reasoning), reflects on past, present and future, and puts information into manageable packets for communicating. The left hemisphere is essential for ‘making sense’ of the more global or holistic information coming from the right hemisphere. Memory retrieved from the right hemisphere is sorted, made sense of and consolidated into permanent memory, in the left hemisphere.

Normal memory storage involves a process in which the sensory and experiential information is mediated by the hippocampus (short and long term memories), and then transferred during REM sleep to the left hemisphere for consolidation into permanent memory. Once experience is encoded into permanent memory, it is available as autobiographical and semantic memory under the control of the higher brain functions.

However traumatic memories are memories which have not been consolidated into permanent memory, but rather have been encoded into implicit, or automatic memory. Some autobiographical memory of the trauma may be stored via the left hemisphere, but there will be many memories of sensory experience and emotional responses, that have been stored in the automatic memory system, beyond conscious control of the frontal cortex. These implicit memories continue to intrude as flashbacks, emotional recall, psychosomatic complaints, acting out, hyperarousal and anxiety responses that are all part of the profile of PTSD.

Creative work uses the right hemisphere (visual imagery, spatial recognition, holistic processing, movement, music and generally non-linguistic representation). Memory is retrieved from the right hemisphere, but implicit, traumatic memories are often not consciously available for retrieval and sorting. However, the creative process, working holistically and non-verbally, can by-pass the subject’s defense system and allow the implicit memories to be expressed through imagery, symbolism and emotional communication.

traumatic memories are often not consciously available for retrieval and sorting. However, the creative process, working holistically and non-verbally, can by-pass the subject’s defense system and allow the implicit memories to be expressed through imagery, symbolism and emotional communication.

Once outside the body, the person’s mind can engage with the imagery to the degree to which they are ready. But some degree of verbalization or language-making is needed, in order for the mind to move the information across to the left hemisphere to be made sense of in language and understanding, and later, to be consolidated into permanent memory. Once these memories are accessible to the higher, or thinking brain, they tend to lose much of their traumatic influence, as they can be reasoned with, challenged, validated and eventually put in the past.

The reason that creativity can be so successful in accessing traumatic memory is the connection between trauma and emotion, and emotion and art. By its very nature, creative work seems to draw on many of the most basic and raw human emotions. Trauma is usually associated with intense emotion, such as fear, anger, shock, disgust and grief. When survivors of trauma begin to allow some emotional expression through art, the brain automatically makes neural links between those emotions and deeper emotional memories that have been intruding unconsciously, and now are given a more direct pathway to consciousness.

and grief. When survivors of trauma begin to allow some emotional expression through art, the brain automatically makes neural links between those emotions and deeper emotional memories that have been intruding unconsciously, and now are given a more direct pathway to consciousness.

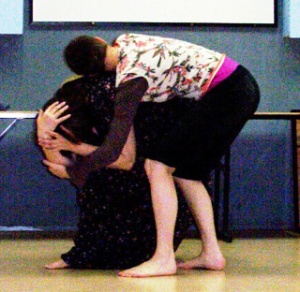

The functioning of the mind can be deeply affected by this process, with some of the thinking and emotional expressions being reorganized through the creation of images, or the meaningful movement of the body, the making of music or dramatic enactments.

TOWARDS A NEUROBIOLOGICALLY-AWARE MULTIMODAL PSYCHOTHERAPY

Where early experience has been either forgotten or compartmentalized, there is a strong need to keep the awareness of these events out of consciousness, so that a ‘normal’ life can be lived. This requires the construction of a system of denial that eventually becomes automatic and very entrenched. Denial may involve full or partial amnesia, memory of the events but denial of their impact and importance, denial of the emotional legacy, denial of the culpability of the abuser, denial of the implicit collusion of the family, denial of the loss of a functional life, or any combination of the above.

The client’s denial system needs to be respected. Through the process of therapy, the client will gradually begin to challenge this system one piece at a time. Art-making and other creative modalities provide a gentle step-by-step way to challenge the denial. The production of images by-passes the barriers that protect the survivor from the truth, and allows them to create images that often surprise – and disturb – them. These images can be gently discussed, always allowing the client to absorb the implications, digest and integrate them at their own pace.

The production of images by-passes the barriers that protect the survivor from the truth, and allows them to create images that often surprise – and disturb – them. These images can be gently discussed, always allowing the client to absorb the implications, digest and integrate them at their own pace.

The images produced by the client can be used as prompts towards education about the dynamics and consequences of abuse – such as the way she/he dissociated to escape the experience, the relationship with the abuser (Stockholm Syndrome) and the relationship with the mother and family members. Present-day consequences that need to be elucidated include the startle and freeze response, the continuing dissociation, the anxiety response, denial system, effect on relationships, career and unmet needs of the Self.

Art-making is a useful adjunct to the task of helping clients take control of their own healing process. The experience of flashbacks can be overwhelming, and being able to self-soothe by drawing one’s feelings is a useful strategy. As traumatic memories arise, representing them visually or kinaesthetically can create a buffer – helping the survivor to remain in ‘observer mode’ so that the trauma is not relived, giving them time to get used to the feelings associated with the memory.

healing process. The experience of flashbacks can be overwhelming, and being able to self-soothe by drawing one’s feelings is a useful strategy. As traumatic memories arise, representing them visually or kinaesthetically can create a buffer – helping the survivor to remain in ‘observer mode’ so that the trauma is not relived, giving them time to get used to the feelings associated with the memory.

For a person who has been conditioned into silence, the use of visual and/or kinaesthetic means of communication serves to bypass the internal injunction not to speak about the details of the abuse. Art-making and creativity utilize the right hemisphere, while verbal language uses the left. Survivors find that they can draw what they cannot speak. It is as if the left hand doesn’t know what the right hand is doing! The therapy process can then encourage them gently to put some words to the picture, sound or movement, and gradually challenge the silence that has been forced on them.

Art-making also serves to bypass the difficulty of verbally articulating the huge conflict built into the victim’s psyche. Over years or decades, the survivor of abuse has had to tolerate the internal conflict, usually by learning to deny and suppress it. The barrier preventing verbal communication of this conflict can be huge, and art-making can provide a means – and its consequent relief – of being able to communicate the conflict – a conflict about which the survivor is often unaware.

Art-making also serves to bypass the difficulty of verbally articulating the huge conflict built into the victim’s psyche. Over years or decades, the survivor of abuse has had to tolerate the internal conflict, usually by learning to deny and suppress it. The barrier preventing verbal communication of this conflict can be huge, and art-making can provide a means – and its consequent relief – of being able to communicate the conflict – a conflict about which the survivor is often unaware.

INTERPRETATION OF CREATIVE WORK IN THERAPY

Interpretation of creative works in art or arts therapy involves the assigning of a meaning to the visual elements of the work. These might include the visual elements of representational objects, such as the way figures interrelate, the size and shapes of figures and objects, their placement on the page, the colours assigned to each, and so on.

In the early days of art therapy, it was common to use a rigid system of interpretation, in which a particular characteristic was routinely given one meaning. An example is the standard art therapy exercise “the three trees” test. Another is the instruction to draw a house, a tree and a person, and to draw interpretive conclusions about the patient’s beliefs and feelings based on the way these objects are depicted. In recent times, art therapists and creative arts therapists (using multi-modal creative styles) are trained in phenomenological methodologies. In other words, they are trained to observe the result of their client’s creativity, and assist them in a process of understanding what it means to them. It is not assumed that one symbol or image has the same meaning for everyone.

It is important to follow creative expressions with linguistic exercises, so that the right-brain experience can move across to the left hemisphere and into language (ie, into explicit memory). Linguistic exercises can include describing the artwork, interpreting the artwork (by the client), writing about the artwork and the feelings that have arisen from it, and discussing the experiences as they relate to both past and present.

SPECIFICS AND EXAMPLES

At a more practical level, the benefits of including creative work in psychotherapy can be presented to clients and trainee arts therapists in the following four categories of experience:

-

Remembering the trauma –

visual imagery can by-pass the traumatic amnesia and allow the client to draw images of the trauma and/or abuse, even if they aren’t aware of remembering the details. It is a powerful tool for bringing deeply buried material to the surface in a safe way.

- Difficulty in speaking about the trauma –

research has shown that when faced with the task of verbalizing traumatic events, the speech centre of the brain (Broca’s Area) can shut down. This is why many survivors of trauma find it so difficult to say what they are thinking and become confused and stressed. Art-making or creative activity again by-passes the speech centre and allows the trauma to be expressed in a different form. Often it can then be gently converted to language.

- Lowering anxiety levels –

art-making and other forms of creativity can be used to lower anxiety levels, through the process of self-soothing. Many people, in the right environment, find creative work very soothing and relaxing. This acts to calm the nervous system, decrease hyperarousal and lower stress hormone levels. This can have a flow-on effect of making the internal mental and emotional processes of therapy easier to cope with.

- Resolving the trauma –

As discussed in the previous section, memory recovery and the construction of narratives through art-making and creativity can assist in resolving the trauma and allowing the person in therapy to move on with their life.

The Arts Therapy field includes a number of creative modalities. Tertiary institutions offer degree courses that qualify graduate therapists in the following forms of creative art: Art therapy (primarily visual art), Arts therapy (some training in visual art, sandplay, dance, movement, music, writing and drama therapy, but not in depth), Music therapy, Dance therapy, Drama therapy, Psychodrama and Narrative therapy.

More on Interpersonal Neurobiology